Feature Stories

Profile

Arieh Warshel is a Distinguished Professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen. He was awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems. Prof. Warshel is a Member of the USA National Academy of Sciences and an honorary member of the Royal Society of Chemistry. He also received numerous awards, including the Tolman Medal in 2003, and the RSC 2012 Soft Matter and Biophysical Chemistry Award, and the 2014 Founders Award of the Biophysical Society. In 2017, Prof. Warshel was invited by President Xu Yangsheng to found the Warshel Institute for Computational Biology. The Institute is intended to become one of the world’s most advanced computational biology centers, nurturing bioinformatics and systems biology talents with comprehensive training.

On 10th May 2023, Prof. Warshel gave a lecture entitled From Kibbutz Fishpond to the Novel Prize at CUHKSZ. This was the first time he visited the campus and met the students and faculty since the pandemic. He used plain language to tell his life journey. To better explain the biology involved, he designed his lecture with specially made animations and adorable memes. After the lecture, Prof. Warshel received an interview with the Fairy Lake. He has a gentle and friendly voice and wore a smile through the whole time. He told the magazine his story and dotted the narration with interesting science facts. Through his words, one can easily feel the care and tenderness this master has for students and younger scholars. We also notice that instead of following a standard path towards success, Prof. Warshel lives a colorful life, which can appear casual or deviant to some. His unique path to the top of his field is a rich source of inspiration to students.

From communal fishponds to Nobel Prizes

Prof. Warshel is a scientist from very humble beginnings. He was born in Kibbutz, a collective farm in Israel. Fishponds were the main source of income for Kibbutz people, who live communally and believe in the ethics of “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”. As a child, Warshel lived with other children in a community called the Children’s Home. He remembers the warm atmosphere there. Children lived in harmony with each other and spent two hours a day with their parents. This is his happy and carefree childhood by the fishponds.

However, Kibbutz did not encourage further education in universities. Children were expected to make contributions to the collective as soon as they can. As a result, they were lagging behind in basic education. Back then, there was no clear learning goals or enough incentives. The only punishment for missing an exam was being excluded from the weekly open-air movie. Moreover, education in Kibbutz focused more on literature and economics. Science courses were few and far between. For Warshel, who grew up with a love of science, the lack of science and engineering in his initial education is a life regret.

Despite the unfavorable conditions, Warshel showed a keen interest in science and managed to explore it in his own way. He made parachutes for cats and tried to make hot air balloons. The relaxed educational atmosphere of Kibbutz made their youth crave for identification in other fields. This led to a surprisingly competitive peer group. Most of them dreamed of becoming military officials or pilots, hoping to make a name for themselves and change the world. The same desire drove Warshel to serve the Israeli Armored Corps, where he studied hard and prepared for the matriculation exam of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He failed the exam and was eventually admitted by the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology.

The next challenge for Warshel was to choose a major. He wasn't sure about what subject he liked or what he wanted to do in the future. An officer friend of his suggested chemistry, for no other reason than that Warshel had good eyesight and could observe experimental phenomena keenly. Warshel took the advice and chose chemistry. Little did he know that this seemingly random choice would become his lifelong passion and pursuit.

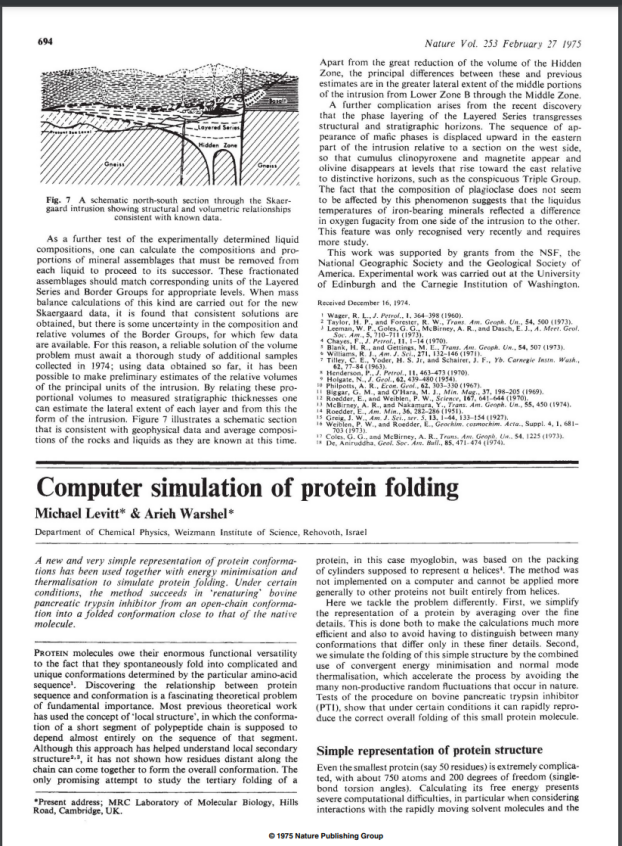

In his third year at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Warshel took part in an experimental program and observed the process of enzyme-mediated chemical reactions. That’s when he became truly interested in chemistry. His undergraduate research project made Warshel realized the cumbersome nature of manual calculations. On the other hand, he was shocked by the power of computers to process data. After graduation, Warshel began his graduate studies at the Weizmann Institute of Science under the tutelage of Shneior Lifson, who is an expert in the use of digital computers to simulate molecular research. Shneior Lifson had decided not to take on any more students, but he made an exception for Warshel and admitted him to a research group that did not exist yet. Since then, Warshel’s research started to get on track. Back then, the combination of new computer technology and traditional experiments was the trend. Its application prospect attracted young Warshel. However, the complexity of protein-related biochemical reactions was beyond the then simulation capabilities of computers. Mainstream academics even thought it impossible to simulate biochemical reactions. But Warshel did not take these assumptions for granted. He decided to test it through experiments. By omitting unnecessary steps and simplifying the structures, Warshel completed the world's first computational modeling of proteins in 1975. In 2013, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his pioneering achievements in this field.

Prof. Warshel’s paper published on Nature in 1975. He was awared the Nobel Prize for his research in multiscale models for complex chemical systems(Levitt, M., & Warshel, A. (1975). Computer simulation of protein folding. Nature, 253(5494), 694-698.)

In his biography, From Kibbutz Fishponds to The Nobel Prize: Taking Molecular Functions into Cyberspace, Warshel shares an anecdote from when he was in the Children’'s Home: Children were required to run one kilometer every Saturday morning. Warshel was often lagged behind in the beginning, but ended up the first at the finish line. This is an epitome of Warshel’s entire life. As a Jewish child from the countryside, Warshel received a poor education in the collective farm. He went through wars, worked in fishponds and restaurants, and enlisted in the army. With ups and downs, he stepped on the path of science with passion and perseverance and went forward step by step. The current world is one with fierce competition. Prof. Warshel encourages young people to have a positive outlook on life, to see competition as a part of self-improvement, and to release full potential through it. There’s more to life than results. The same optimism has been present in Warshel’s learning and researching. To this day, he is still working tirelessly in the pursuit of pharmaceutical research and development.

Ten years after the Nobel Prize: There Is No Ultimate Goal

Two thousand and twenty-three marks the tenth year since Prof. Warshel was awarded the Nobel Prize. In the past decade, he worked on enzymes involved in different diseases. By understanding how they work and predicting their changes, better drugs/medicine can be developed. In his view, the word “destination” is kind of pessimistic. In his research, there is no so-called ultimate goal. He is still aiming at more accurate drug predictions and exploring the frontiers of science where few could reach.

In the history of biomedicine, drug resistance has been a huge challenge for scientists. Over time, the efficacy of antibiotics weakens. To address this problem, Prof. Warshel and his team for drug development and biological mechanism studies using computational modeling. They are also making practical advances in studying covalent inhibitors. For Prof. Warshel, the study of enzymes is as much about solving problems as it is about the sheer joy of scientific discovery. “We just keep applying our approach to different interesting problems and having fun in doing it.” Just as he was driven by curiosity to study hot air balloons and parachutes as a child, Prof. Warshel keeps his curiosity and awe of the unknown, which have driven him to conquer one challenge after another.

Today, the boom in artificial intelligence is bringing opportunities and challenges to scientific industries. On this topic, Warshel sees the future trends of biomedical field and has his concerns. In his opinion, misuse of or over-dependence on AI could impede people’s understanding of the nature of science. “What intrigues me is always how enzymes work, not AI.” He believes that AI constructs a chasm between science and the general public. The more people rely on AI to solve problems, the more they are likely to neglect learning and understanding basic science. This will push the public away from science, instead of bringing the two closer. He also doesn’t think the recent boom in combining AI with other fields, such as biomedicine, necessarily represents the right direction. “AI is similar to brute force.” Prof. Warshel remains skeptical about how much people can actually learn from the rapidly advancing AI technology.

The Dream of Shenzhen: A Message to the 10th Anniversary of The Chinese University of Hong Kong ,Shenzhen

Prof. Warshel has been an Honorary Professor at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen since 2014. In 2017, he led the establishment of the Warshel Institute for Computational Biology. Over the past nine years, he witnessed the development of the university. He has spoken to students with his best wishes and high expectations on numerous occasions, including inauguration and graduation ceremonies. He has, for many times, given lectures and held seminars for students and faculty, sharing his research experience and achievements. Each time, students join in the discussion actively and raise relevant questions. Prof. Warshel has also expressed his recognition for the international teaching in CUHKSZ time and again. He thinks students here are very expressive. Young as undergraduates, they are able to discuss science freely in English. Conversations with them always make him feel welcomed and energized.

Prof. Warshel speaking at CUHKSZ

“Shenzhen is the most energetic and attractive city my wife and I have ever been to. My co-workers here are down-to-earth and energetic. I love doing research with them.” The city’s generous support for research and emphasis on talents and knowledge appeal to Warshel. He is also impressed with the faculty and students at CUHKSZ because of their passion for science and diligence. Before the pandemic, Warshel used to visit Shenzhen up to four times a year. He puts great efforts in cultivating his research team and planting the seeds of scientific research in Shenzhen. Now that the epidemic is over, he has returned to the campus as soon as possible. He shares stories of his research and provide guidance to young people who are interested in scientific research. Prof. Warshel hopes that students and faculty here will stay curious, persistent, and persevering and keep pursuing their career.

Prof. Warshel has great expectations for the development of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. He believes it will evolve into a major scientific center by virtue of its interdisciplinary integration. He is looking forward to the 10th anniversary of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen. “The progress and development of CUHKSZ goes beyond my imagination. I hope that it will continue to move forward and establish itself as a first-class university in China and worldwide. I also especially hope that the medical school will get better and better, which I believe they can do.” What’s more, he said that the Warshel Institute for Computational Biology, based in the rapidly developing Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, will make significant contributions to the development of biomedicine by combining basic research and technology application, using computational methods to understand the molecular basis of diseases, and exploring various therapies.

Reporter/Dong Chupei, Liu Yezhou

Writer/Dong Chupei

Editor/Hu Yixiao